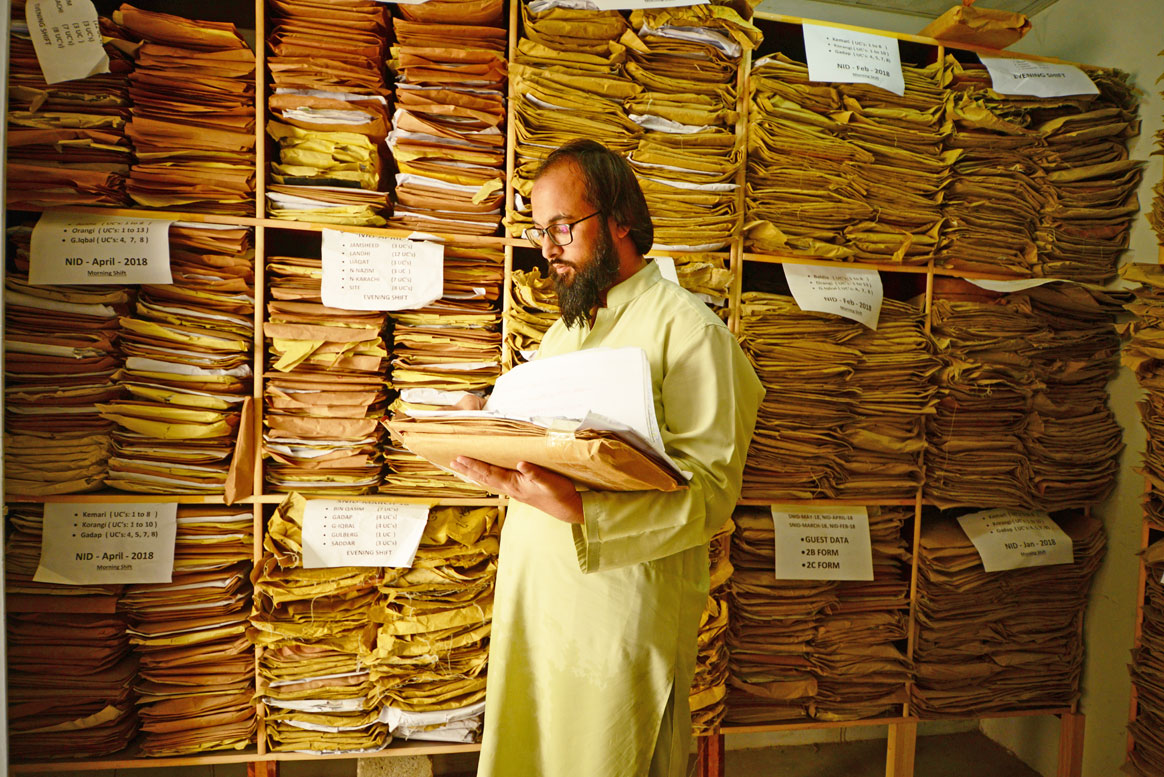

Form by form, campaign by campaign, data handlers like Jan, Ali, and Bilal are helping to end polio.

As the sun sets across Sindh province, exhausted polio eradication volunteers head home after a busy vaccination campaign. Each has personally vaccinated hundreds of children. In total, it has taken just a week for 9 million children under the age of five to receive two drops of oral polio vaccine, boosting their immunity against the virus.

In the crowded office of Jan Sayyed, Ali Raza and Muhammad Bilal Wasi Jan however, work is only just beginning. They work in the Polio Eradication Data Support Centre, located in Pakistan’s biggest city Karachi. During the campaign, vaccinators fill in paperwork every time they distribute vaccine drops. They record the number of children reached with vaccines, their existing vaccination status, any vaccine refusals and whether the children are local to the area, or visiting.

Across a typical vaccination campaign, this generates data referring to over two million children, recorded on thousands of forms. It is the challenging job of Jan, Ali, and Bilal to label and classify all this data so that it can be uploaded to an online system and analyzed to improve the next campaign.

Data is the lifeblood of the polio programme

Waqar Ahmad, Technical Officer for Data at WHO Pakistan, believes that if immunization and disease surveillance represent the heart of the programme, then data is the lifeblood that helps the programme inch closer to vaccination.

Different kinds of reliable data help the programme make decisions based on evidence. For instance, data that shows a high rate of vaccine refusals in one area allows the programme to investigate the cause further and act to persuade parents of the importance of vaccination.

But creating effective systems for gathering, sorting, and analyzing high-quality data hasn’t been easy. It has required rethinking approaches, overcoming bumps in the road, and thinking beyond the usual parameters of data management.

Pakistan’s polio data journey

Data collection and record keeping in Pakistan’s polio eradication programme began in 1997. Originally, data was collected only in very specific circumstances, such as when cases of Acute Flaccid Paralysis were detected. Such limited data collection meant that broader programme activities could not be analyzed, which increased the chances that vaccination campaigns could be ineffective. Data on other aspects could ensure that logistics were right-sized, and that human resources were deployed where they were most needed.

In November 2015, the programme introduced an online database designed to provide real-time data, named the Integrated Disease Information Management System (IDIMS).

The IDIMS database is used to store pre-, intra- and post-campaign data relating to multiple areas, including vaccination, disease surveillance, human resource planning, logistics planning, and mobile data collection. Data inputted into IDIMS is directly available for viewing and analysis at the provincial, national, and regional level. It can be cross-referenced with other polio eradication databases.

Young Pakistanis like Jan, Ali and Bilal are part of the workforce that keeps the whole system online. Once they have labelled and classified the paper forms, they pass the data onto their colleagues to be digitized and analyzed.

Gender innovations

Gender-disaggregated data represents a new area of work for the data management teams. Data included in the IDIMS database assists with gender-conscious campaign planning at the provincial level, while a separate system analyses gender-disaggregated information at the country level. Ensuring female vaccinators are recruited for campaigns is crucial, as women can often vaccinate children in places where for cultural reasons, men cannot.

Increasing user-friendly interfaces

As part of efforts to make systems user friendly, one year ago the polio programme launched online data profiles for Union Councils (UCs), the smallest administrative units in Pakistan. These profiles are available on the National Emergency Operation Centre data dashboard and allow polio programme staff to easily extract sizeable amounts of data about the local epidemiological situation within 30 seconds, as well as compare and analyze data for the past six years.

One of the most useful, innovative aspects of the UC profiles is that they collate information on children who were persistently missed during the last six campaign rounds, with information like contact details and the immunization history of the child. Such information assists the programme in follow-up engagement with the child’s parent or caregiver to encourage vaccination.

This requires speedy information sorting and uploading. Jan notes that his team is filing information more efficiently than they used to. This helps to ensure that details are up to date for nearly every town and village.

Over the coming months and years, further innovations will be introduced to improve data efficiency, range and quality.

Campaign by campaign, form by form, data handlers like Jan, Ali, and Bilal are helping to end polio.